“Oh, Mr Hemming, what’s happening to the world? What’s this filth that’s… flooding… everything… ”

“Oh, Mr Hemming, what’s happening to the world? What’s this filth that’s… flooding… everything… ”

In the late Sixties and early Seventies, it was examination time for the British public school system. A succession of uncomplimentary and fascinating films each, to a greater or lesser degree, depicted or predicted the violent clash that was happening between the unchanging, cloistered solemnity of British high society, and the values of a new generation, impatient at the constraints and procrastination of the old order. The unchanging, cloistered world of private education was the perfect metaphor.

This was not the same region of the Sixties that had produced the mini, the miniskirt, The Beatles and Twiggy. This was a darker realm, daily growing dimmer with disillusionment as the decade drew to a close and a generation realised that, in the words of Danny the Dealer in Withnail and I (1987), “the greatest decade in the history of mankind is over and… we have failed to paint it black”.

This was not the same region of the Sixties that had produced the mini, the miniskirt, The Beatles and Twiggy. This was a darker realm, daily growing dimmer with disillusionment as the decade drew to a close and a generation realised that, in the words of Danny the Dealer in Withnail and I (1987), “the greatest decade in the history of mankind is over and… we have failed to paint it black”.

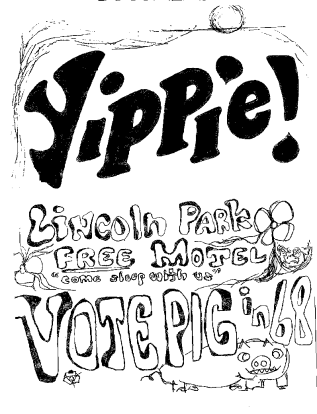

Whereas the mid-Sixties had sparkled with joy at populating itself with working-class heroes in music, fashion and film, that friendly revolution was now giving way to something more aggressive. As the thuggish Nixon presidency began to make itself felt, the chaotic Youth International Party, a directionless but attention-seeking crew of  American anarchists, spoke of a “new society”; when they hijacked The David Frost Show in 1970, leader Jerry Rubin claiming that “capitalism is just another word for stealing”, a blimpish member of the audience asked in disgust: “how many seconds tomorrow will these people spend anywhere near a cenotaph?” The generation gap was at its widest. Student revolts at the new universities and ugly demonstrations in Grosvenor Square suggested that the fag end of hippydom was lighting a dangerous fuse. Mike Rutherford, future member of Genesis, has said that throughout his time as a pupil at Charterhouse in the Sixties, he was banned from playing the guitar, his housemaster seeing the instrument as a symbol of an imminent revolution. The private school was the perfect dramatic arena in which to explore this clash between the old order and the youth of the day, an unchanging shrine to English conservatism, class hierarchy, repression and corruption.

American anarchists, spoke of a “new society”; when they hijacked The David Frost Show in 1970, leader Jerry Rubin claiming that “capitalism is just another word for stealing”, a blimpish member of the audience asked in disgust: “how many seconds tomorrow will these people spend anywhere near a cenotaph?” The generation gap was at its widest. Student revolts at the new universities and ugly demonstrations in Grosvenor Square suggested that the fag end of hippydom was lighting a dangerous fuse. Mike Rutherford, future member of Genesis, has said that throughout his time as a pupil at Charterhouse in the Sixties, he was banned from playing the guitar, his housemaster seeing the instrument as a symbol of an imminent revolution. The private school was the perfect dramatic arena in which to explore this clash between the old order and the youth of the day, an unchanging shrine to English conservatism, class hierarchy, repression and corruption.

“If the Church of England is the Tory Party at prayer, the public school system may be called the Tory Party in the nursery. Here are set out the traumas, deformations and truncations of character that explain the British establishment. The British are known to be mad. But in the maiming of their privileged young, they are criminally insane”. (John le Carré)

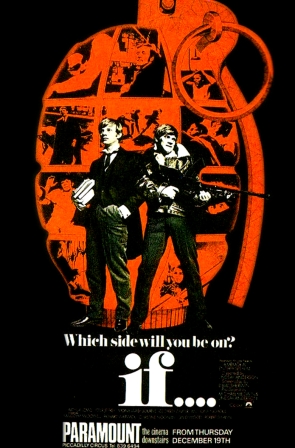

A couple of decades later, I was nearing the end of a miserable sentence at a shabby, gloomy independent school when, as if to complete my education there, I fortuitously discovered this strange spray of school-based dramas. The most celebrated and significant is undoubtedly If…. (1968). Originally a script called Crusaders by ex-Tonbridge pupils David Sherwin and John Howlett, director Lindsay Anderson turned it into an eccentric, outrageous fantasy so acutely English—and so gleefully iconoclastic—that only the French dared give it an award, when it became the first British film to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

While If…. was very much the counterculture in action, the other tales out of school were not romances about revolution but simply prescient pieces of storytelling. What is striking about them all, however, is the lack of reverence for their public school settings: what had once been a respected symbol of the British establishment was now more often portrayed as a nasty nest of disreputable youths corrupted by privilege. In John Mackenzie’s commendable 1971 film version of Giles Cooper’s classic radio and television play Unman, Wittering and Zigo, a new teacher at a boys’ school struggles to keep control of his class on his first day, and when he threatens detention, is told quite calmly by them that this is not advisable: his predecessor did that, and “that’s why we killed him”.

Suddenly not all children on screen were The Railway Children. This breed were dangerous, scheming, impervious and amoral, the children of Lord of the Flies, the school their desert island. It is telling that even Jack Gold’s little-known but riveting Good and Bad at Games, William Boyd’s story of bullying at a boys’ boarding school, although filmed in 1983, is actually set in 1968.

Suddenly not all children on screen were The Railway Children. This breed were dangerous, scheming, impervious and amoral, the children of Lord of the Flies, the school their desert island. It is telling that even Jack Gold’s little-known but riveting Good and Bad at Games, William Boyd’s story of bullying at a boys’ boarding school, although filmed in 1983, is actually set in 1968.

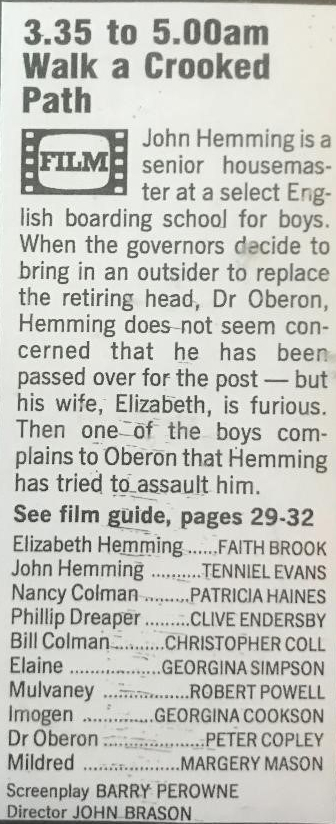

The most obscure of all the films in this mini-genre, however, is Walk a Crooked Path (1968). That likeable, modest and always surprising actor Tenniel Evans (once a teacher himself), in a rare leading role, plays an uncharacteristically shadowy character, English master Hemming, a haunted man emasculated by his disillusioned, hectoring wife Elizabeth (Faith Brook). Set in a minor (and rather sparsely populated) boarding school, the story begins with Hemming being passed over for promotion once again.

At his house within the school grounds, his priggish housekeeper Mildred (Margery Mason) prepares the evening meal with her mini-skirted, uninterested niece, Elaine. One of the pupils, the dislikeable Dreaper (Clive Endersby) arrives to collect an essay. Concealed in the exercise book is a wad of banknotes. Hemming invites Dreaper to walk with him to the library. When Dreaper returns to the dormitory, he is bleeding and bruised. To the other boys’ disbelief, he accuses Hemming. “That bugger’s bent”, he yells.

The Hemmings eat in an atmosphere of loveless monotony, drinking the last of the fine wine they were given as a wedding present long ago. “When there’s something to celebrate, any wine’s good. When there’s nothing to celebrate, good wine’s a comfort”, Hemming explains. Mrs Hemming reveals that she knows that after seventeen years of undistinguished service, he has once again lost out on a promotion. Her tormenting of him is interrupted by a telephone call summoning him to the Headmaster’s office. “What have you done?” she cries in dread.

In a scene that would be unthinkable today, Dreaper has to repeat his accusation before both the intimidating Headmaster and Hemming himself. Meanwhile, Mrs Hemming works herself up into a frenzy while her friend Nancy (Patricia Haines), in a similarly spiteful marriage to a fellow teacher, tries to console her but also to prepare her for the worst: her husband may be facing not only public ruin but prison. Driven to distraction, Mrs Hemming takes flight in her car, drunk and hysterical. Elaine, seemingly sympathetic, attempts to seduce a confused Hemming when he returns home, but when he rejects her, she scornfully looks down at him and says: “… and I didn’t believe them…”

Mrs Hemming drives off the road and is killed. Hemming takes a melancholic midnight walk through the school grounds and weeps. The following day, Dreaper’s errant, frivolous mother (Georgina Cookson) arrives at the school, and is asked to have a heart-to-heart with her son, but behind closed doors we see the true dynamic of their relationship, as Dreaper cooly demands money, takes what is in her purse, and when she feebly asks if there is anything she can do regarding this “… thing that’s happened to you”, replies “sure. You can send me my allowance. Regularly”.

Although Dreaper drops the charge, Mrs Hemming’s funeral is poorly-attended, and Hemming decides to resign and move away. The only person who shows any faith in him is his housekeeper, who despairs: “what’s happening to the world. What’s this filth that’s flooding everything?” However, once she’s gone, Hemming is visited by Nancy, who is revealed to be his lover. Although the plan had only been to create a scandal virulent enough for Mrs Hemming to divorce her husband, the resultant suicide has only worked in their favour, as Nancy uneasily acknowledges.

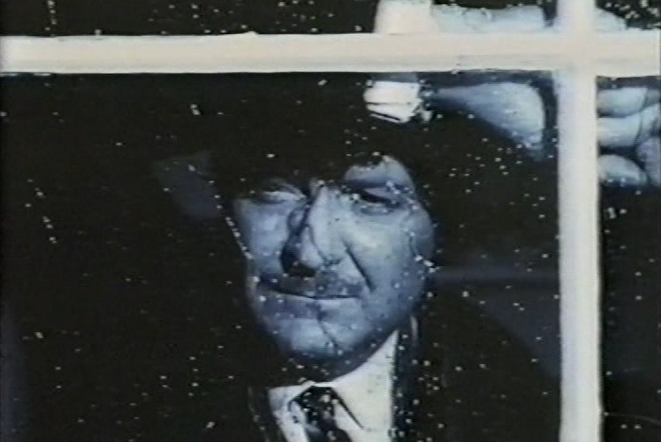

However, the story takes an even darker turn when Hemming recalls “roughing up that boy in the wood… it was a strange experience”. His wife’s legacy will allow him to move to the South of France, a place he visited as a boy, a time which he “has been thinking a lot about lately”. “When everything is quite safe, I’ll leave Bill and come and join you,” she says, but he is barely listening. As he begins to talk about that holiday’s significance, and of his swimming naked with the other boys, the camera slides down behind his chair, so that we watch Nancy’s gradual realisation of the truth about her lover’s sexuality through a wicker lattice, an echo of the criss-cross of the leaded windows reflected on Elaine’s face during the seduction scene. Nancy leaves, returning to her husband who, because of Hemming’s departure, has been promoted to Head of House. She looks at him, resigning herself to make the best of what she is left with, and kisses him.

Dreaper arrives to collect his second payment from Hemming for his part in the conspiracy. “You’re fond of money, aren’t you Philip,” Hemming says. “Well I shall have plenty of money now”. Hemming then suggests that Dreaper, about to leave school, might care to join him “for the summer. It would give me great pleasure, Philip”.

“What would it give me?” comes the reply. When Dreaper starts listing his demands, they are far beyond the means of Hemming. “Cheap hotels, long walks… that’s not for me,” says Dreaper. “I know what I want, and you’ve shown me how to get it. I’ve got my plans all made… and not with a washed-up schoolmaster”. He leaves Hemming broken and alone.

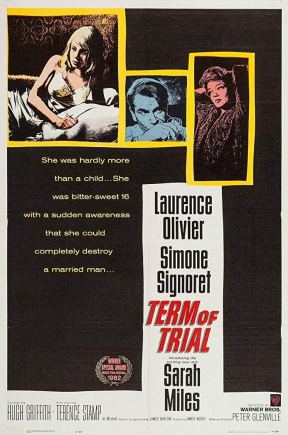

“Po-faced melodrama in a minor key, quite effectively done,” was Leslie Hallwell’s uncharacteristically positive review of a film that is a relic of a different time in more ways than one. Its tortured portrayal of homosexuality and queasy depiction of abuse allegations make it a disturbing reminder of how unenlightened that permissive age was for the most part. Where the film scores highly is in its depiction of the schizophrenic nature of those times, of the clash between the generations, the hypocrisy of the old and cynicism of the young, and of the corrupting power of an increasingly materialistic society. It is  fitting that the final and most powerful image of the film is of Hemming murkily seen through a rain-drenched window, promising foul weather ahead. Melodrama it certainly is, with its Gaslight-style plot, although its closest parallels are two earlier school-based dramas, The Children’s Hour (1961), about two teachers accused of having a lesbian affair, and Term of Trial (1962), in which henpecked teacher Laurence Olivier is accused of molesting an infatuated girl pupil (Sarah Miles).

fitting that the final and most powerful image of the film is of Hemming murkily seen through a rain-drenched window, promising foul weather ahead. Melodrama it certainly is, with its Gaslight-style plot, although its closest parallels are two earlier school-based dramas, The Children’s Hour (1961), about two teachers accused of having a lesbian affair, and Term of Trial (1962), in which henpecked teacher Laurence Olivier is accused of molesting an infatuated girl pupil (Sarah Miles).

I spoke to Clive Endersby, the Canadian child actor (and now writer) who played the loathsome Dreaper, the avaricious young sociopath who appears to be more premonition of the Eighties than child of the Sixties.

“When I got the part, they added in a few lines to explain my accent. I had come to Britain at the end of 1959. We were an acting family back in Canada; my father had been in showbiz all his life—he was a champion ballroom dancer—and I had started acting

when I was nine. But there was only so much work in Canada, with only one tv station. I got a scholarship to the dreadful Aida Foster Theatre School in Golders Green, which had a pink uniform; the only nice thing was that there were 400 girls and 25 boys! I worked in the West End and on television, then John Brason, the director, saw me in something and cast me in Walk a Crooked Path. I liked him; he would say that I was always looking mean, with my eyes down, so by the end of the shoot he was just saying “oh, just give us your heavy-lidded look!”

Contemporary reviews and, from the late-night screening I caught at the end of the 1980s,  the TVTimes, all mention that there were considerable production difficulties with the film. It had in fact twice been commenced and twice abandoned, before finally, everything that had been shot was scrapped, along with all but three of the cast and the composer, Leslie Bridgewater. “There were rumours that the investors hadn’t got what they wanted from the original director, so rather than write it off, they said to John Brason: ‘can you do a movie in eight weeks?’ It was written by Barry Perowne (apparently a pseudonym for novelist Philip Atkey) in about a fortnight. John was a director who got conned into producing it too. Though it makes no difference to the audience, it was a miracle it turned out the way it did. Actors were sharing trailers because the budget was so tight. We had limited access to the school where we filmed (Ewell Castle School in Surrey—former pupils include Oliver Reed), and some people were just hired for the day, to get them in and out as cheaply as possible.

the TVTimes, all mention that there were considerable production difficulties with the film. It had in fact twice been commenced and twice abandoned, before finally, everything that had been shot was scrapped, along with all but three of the cast and the composer, Leslie Bridgewater. “There were rumours that the investors hadn’t got what they wanted from the original director, so rather than write it off, they said to John Brason: ‘can you do a movie in eight weeks?’ It was written by Barry Perowne (apparently a pseudonym for novelist Philip Atkey) in about a fortnight. John was a director who got conned into producing it too. Though it makes no difference to the audience, it was a miracle it turned out the way it did. Actors were sharing trailers because the budget was so tight. We had limited access to the school where we filmed (Ewell Castle School in Surrey—former pupils include Oliver Reed), and some people were just hired for the day, to get them in and out as cheaply as possible.

“Tenniel was very quiet, but such a good actor and very subtle. I heard some people say he was a little too subtle for the role, but I thought he was perfect; I was stunned by his quality. Let’s face it, it was a B-film, but rather than it being over the top, there’s a streak of honesty going through it, and that’s thanks to those actors.

“Tenniel was very quiet, but such a good actor and very subtle. I heard some people say he was a little too subtle for the role, but I thought he was perfect; I was stunned by his quality. Let’s face it, it was a B-film, but rather than it being over the top, there’s a streak of honesty going through it, and that’s thanks to those actors.

“As for the controversial aspects of it, Barry was a very nice man but he never struck me as a revolutionary, just a competent pro who could deliver a movie quickly and efficiently. Maybe what happened is they set up the story with me complaining of being assaulted as a good hook, and then thought ‘now what do we do to get out of this?’. They may well have just been wanting to do something original; what might seem progressive may have just been driven by the desire to give the story an ending”.

Monthly Film Bulletin, always happy to give credit where it’s due, praised the film, but noted its “dire lack of light relief in the otherwise capable writing. This is so noticeable that when the solitary witty line emerges, it seems, although perfectly in keeping with the subject matter, almost incongruous. (A deputy, greeting two guests in the Headmaster’s absence, explains cryptically: ‘I’m his temporary vice’.) This line, incidentally, is given by Barry Perowne to himself”.

Kine Weekly, while praising the film, judged it “an ugly picture of conditions in a so-called reputable boarding school,” while Variety noted that “in recent years British film-makers have had lots to say on the subject of exclusive boys’ schools, and in a number of cases it has resulted in forthright examinations of the psychology of tradition and how well it stands up to the burgeoning pressure of society in transition. As a sort of microcosm of the upper class, the boys’ school affords the scripter with a prodigious quantity of angles”.

Although to modern eyes the film at times looks like Goodbye Mr Chips as if directed by Pete Walker, Walk a Crooked Path not only captures a sense of foreboding at the morals of a new generation; it also depicts the queasy causes and effects of corruption. Sterility and repressed sexual desire corrupt Hemming, but there is also a sense that it is not just acquisitiveness that corrupts Dreaper, not just that he is the product of irresponsible, materialistic parents, but that the school itself is also a corrupting influence, showing no loyalty to a long-serving and dutiful teacher, sweeping aside a serious allegation, turning the boys into scheming, amoral monsters and the few women within its confines into cynical manipulators or conniving harridans.

Any institution with a high price of admittance and a veneer of respectability is vulnerable to corruption. It was an ugly fact of life at my school that violent bullying was frequently followed by a parent rich in funds but poor in morals paying the school to say no more about the incident. This taught a significant number of the pupils first-hand the mantra of the era, that “greed is good”. It is no surprise that the City was the traditional route many of them took after leaving; there was even a direct train from the station five minutes away; you could be at Liverpool Street in half-an-hour, a real home from home.

EM Forster wrote that boys that attend public schools leave with “well-developed bodies, fairly-developed minds and under-developed hearts”. There was no love in that environment, no kindness, no compassion and no encouragement. A couple of years after leaving, a friend said to me: “we spent seven years in a world of hatred”.

Watching Walk a Crooked Path again not only prompted me to write about it; it also reminded me of those unhappy, unkind times. I would have seen the film for the first time just as I was entering the Sixth Form, a slightly more relaxed period, thanks to the sudden civilising influence of girls after five years of single-sex classes. In their own ways, Walk a Crooked Path and If…. had vivid, instructional influences on me, throwing a critical spotlight on the world I’d occupied for so long. Revisiting this film led me to revisit the school, and to see again (and thank) my English teacher, to whom I am indebted.

I am glad I went back. Instead of an unloved, neglected place that was crumbling both physically and spiritually, I was shown something unimaginable thirty years ago, a place rich in facilities and opportunities, where teachers are civil to children, where children co-operate with one another, where creativity is encouraged and endeavour is facilitated. I don’t imagine it to be utopia, but the contrast between the gruff 1980s, when the place had no sparkle, no optimism and little zeal for learning, reeking of bigotry, bullying and corruption, and today’s more educated and enlightened world, was astounding. I can’t pretend I didn’t feel a trace of envy for today’s pupils, but more a sense of relief that the world has become more accountable, and, I think, a little more compassionate. I learnt some unsavoury lessons about life as a pupil there, but I learnt a better one when I returned as an adult.

My sincere thanks to Cliver Endersby for taking the time to share his memories.

A fascinating review and analysis not only of the film but of the society it depicts. What was true of your experiences in the 80s was even more true of my experiences as a scholarship boy at a public school in the 50s. Prefectorial beatings and other sanctioned bullying, snobbery, repression, and many incompetent teachers mean that life was a daily misery. It was a schizophrenic experience living in a Tom Brown world during the day and a world of Elvis and James Dean outside. Horrible times.

LikeLiked by 1 person