“Mary, Mary, quite contrary, how does your garden grow? With silver bells and cockleshells, and pretty maids all in a row.”

I was recently asked by a creative writing student how one copes with rejection in this business. As an actor once said, you must be half in love with rejection to do a job in which you will get more rejections than a Jehovah’s Witness. After that initial disappointment, frustration or sense of unfairness when decision-makers are indifferent to something that you have lovingly crafted, one in time moves on, lets it go, discovers new fascinations. However, there will always remain the occasional obsession which you regret was never to be shared with an audience. I have lifted a bundle of papers from the bottom of a box at the bottom of a cupboard, to finally give a home here to one such unwanted story.

For those of us whose childhoods were happy, in recollection elements of them remain idyllic. I have just completed a new book, which tells a story much graver than this one, but towards the end of it I had occasion to mention the long-since passed “Crazy pub” in Hertfordshire, a roadside fun palace crammed with knick-knacks and bric-a-brac, something of a monument and testament to an age when novelty and frivolity were in fashion, an time of curiosity and eccentricity which has long since passed. I used to feel that childhood ended abruptly for the adults I grew up around, whereas now, in an age of gaming and cosplay, sci-fi conventions, graphic novels and adult colouring books, it seems that it can last a lifetime for those who wish it, but this is an unfair and over-simplistic judgment. While adults were most definitely “grown-ups” when I was little, and most had firmly put aside childish things in exchange for driving licences and mortgages, there were certainly more eccentrics colouring the landscape back then too, a little more home-grown frivolity.

My childhood summer holidays were spent in Banffshire. Cullen, where my father hailed from, was to a child a toytown, a coastal wonderland, the home of an auntie who made the best scones and an uncle who told the best jokes. Just along from Cullen, on the road into the dainty fishing village of Whitehills, lay a cottage which was to me the most magical place on earth.

Craigherbs Cottage sat by itself, just past a crossroads, in a hushed spot overlooking the sea and separated from the village by bright and swaying fields of barley. The front door, windows and gate were painted in rainbow colours, and the garden was a blaze of red, white, blue and yellow. It was all wonderfully described by the Garden News in 1976:

“The fairies at the bottom of Annie Thomson’s garden need never get lonely – not with a couple of lighthouses, a sprinkling of sailing ships, the odd cuckoo clock, ducks, rabbits and a milkmaid for company. Before you jump to the conclusion that my mind is wandering, let me hasten to add that they are all ornaments. Alone they would make an eye-catching display, but Annie’s little acre is also a dazzling splash of colour with thousands of blooms juggling for position in a veritable magic rainbow land.”

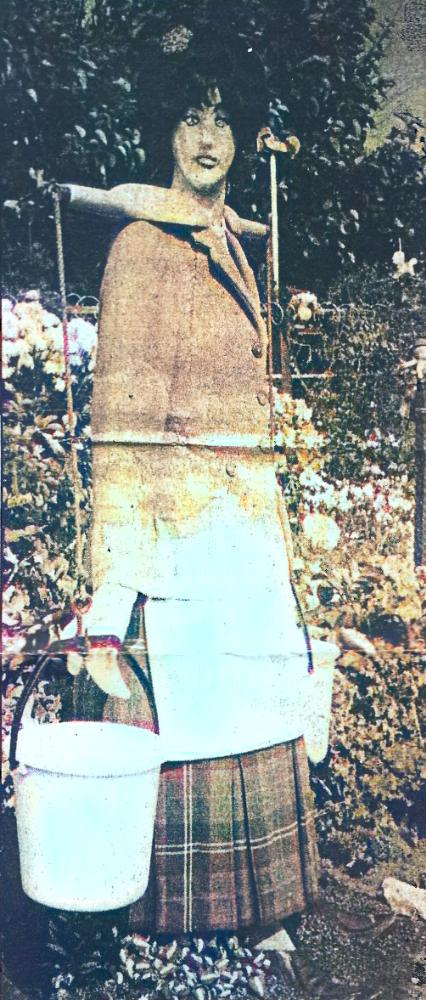

Amid the immaculate lines of flowers was a dazzling community of the peculiar. An array of spacehoppers on poles at the back peered down at ornate nesting boxes for wild birds, a ship’s cabin, windmills, stone animals and birds and, almost camouflaged amid the colour, three life-size, smartly dressed mannequins: at the back, a girl playing a guitar, by the well, a maid carrying two pails suspended from a yoke across her shoulders, and, seated and helmeted, another steering a wheel, adorned with crash helmet and goggles. It might sound sinister but in fact there was not the slightest twinge of eeriness about it; the setting was so delightful, the displays so charming, the care devoted to it all so impressive, that it was simply enchanting.

The other overwhelming memory of that cherished spot was the silence. There was a stillness that remained unbroken however long one dwelt there, a quietness that could be listened to.

To a child it was yet another of the wonders of that wonderland, and the most fascinating of them all. I was forever asking if we could go and see “the lady who makes figures”, whom I discovered was in fact named Annie Thomson, and had been to school with my Uncle Alan.

Each summer, as we headed up to Scotland, I would wonder with trepidation whether Craigherbs Cottage was still in bloom, and so it was, all through my childhood and even my years spent close by at Aberdeen University. Then, when visiting my uncle in 1995, I was told that Annie had suffered a stroke and was now in a local geriatric hospital. She died in 1996.

We now move forward to Christmas 2003, which I am spending with my parents, now retired and living in Banffshire. I had just sold my first radio play to the BBC and was looking for ideas for the next one. It struck me that there might be a story to be found in my memories of Craigherbs Cottage. That afternoon, I took a bus into Whitehills, to see if any of the older folk could tell me just who Annie Thomson was, and how her magic cottage came to be.

I struck lucky. At the bus stop two ladies readily shared their memories of her, and pointed me to a nearby house, assuring me that the old man who lived there would have much to tell me. Over a tray of tea and biscuits he told me a little of her extraordinary story. From there, I placed a request for information in the local newspaper and was overwhelmed by the response. People wrote me long letters, enclosing photographs and press cuttings. All these ingredients resulted in a radio script, Silver Bells and Cockleshells. I approached the delightful Hannah Gordon to play Annie; she loved the script, knew the area, and understood the character. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be, and after a clutch of rejection slips from BBC producers, the script was put aside. Now, nearly 20 years on, I am brushing the dust off the letters, cuttings and photographs to give a home here to the story of Annie Thomson and Craigherbs Cottage.

Annie Maria Thomson was born in 1911; she and her brother David were raised on a croft called Howlands, near Culvie, about eight miles inland from her future home at Craigherbs Cottage. As a girl, she would accompany her father on a long walk every Sunday evening to Craigherbs, then a smallholding, for a weekly barter. Annie left school at 13 and went into service at the local manse.[1] Her parents moved to the cottage in 1932, keeping two or three cows and some poultry. In the Second World War, Annie joined the Land Army, for which she was awarded a certificate of appreciation from the then Queen Elizabeth, and which she kept for the rest of her life. One villager told me she had a vague memory of Annie having a fiancé who was killed in the war. After war service, she joined her parents at Craigherbs, while her brother, who had served in the RAF, became a gardener on an estate in Aberdeenshire. After her parents died, she lived there alone for the rest of her life.

The two-roomed “but and ben” cottage, rented from the Earl of Seafield, comprised of a living room/kitchen, a small bedroom and a lobby. It had no amenities whatsoever – no running water, no gas, no electricity. Annie lived almost entirely in one room, where there was a coal fire with small ovens on either side. One woman told me that tea from the kettle made with dry tea leaves tasted wonderful, and that Annie would read fortunes from the leaves afterwards. Lighting was by Tilley lamp and candle. Entertainment came from a battery radio, the People’s Friend and the local newspaper. Heating was from the open fire, though she also had a gas heater and a paraffin stove, and, according to one villager, “an extra cardigan, if necessary, but Annie was hardy”. There was the occasional coal delivery but chiefly she gathered fuel from the little wood nearby. From time to time a bag of peats would be left at her door by a friendly soul.

There had been a well in the next field, but modern heavy machinery caused drainage problems and it closed up, so from then on, she relied on water from neighbours and collected rainwater in a barrel. In later years, a cold-water tap was installed in the yard, her only concession to modernity, although she insisted that the water from it was never as good.

Each morning, before the fire was lit, her first cup of tea of the day was made on a small one-ring camping stove. In later years, a friend who passed each morning would bring her a flask of boiling water to start her off. Also, at some point, a small caravan appeared in the garden which was used for storage and for washing up. She spoke Doric freely and “her weather forecasting was reliable”. She adored tartan, and was usually attired in tartan trousers and bonnet. Her one treat was regularly having her hair done in the village. Her only other indulgence was her dog, a Pekinese which she spoilt shamelessly, first Bobby and then Ricky. They both in turn had their own house in the garden with their name about the door. Half a mile along the road stood Ladysbridge mental hospital. One would often see people in outdated clothing chatting on the little seat by the crossroads or wandering along to admire the garden; Annie befriended them, and they would take her shopping list down to the grocer’s, to be rewarded with “a cuppy of tea and a piece.”[2]

But how did this hardy lady, living such a lowly lifestyle, come to create that extravagant spectacle of a garden? The Garden News article of 1976 related how Annie had been “weaving her spells at the whitewashed-walled Craigherbs Cottage” ever since an accident a decade earlier, when a favourite ornament shattered on the cottage’s flagstone floor. She repaired it as best she could, but it did not bear close inspection, so instead she placed it in the garden. Once it was there the idea was born of rescuing other unwanted or broken oddments and ornaments. A villager gave her a model aeroplane, another gave her a stone bird. And so it began. As the population of the garden grew, her next step was to start making her own novelties and planning out floral displays that would best showcase them, and so what had previously been a vegetable patch was gradually conquered by colour and eccentricity, reality by dreams, practicality by magic.

She made nesting boxes for wild birds and lined them along the hedge. Maritime items washed up there; she hung old floats from fishing nets, and a circle of yachts sailed around in the wind on a bicycle wheel fixed to a pole. The dummies were cast-offs from the draper’s shop in Whitehills, on which she painted faces and hung clothes. Even the paint and the old clothes were donated by people, contributing to this masterpiece of make-do and mend in an age before anyone had heard of recycling. Each year, as the days shortened, the figures were brought inside for wintering, Annie kept busy throughout the cold months with repairs and with creating new wonders.

As word spread, the cottage became a tourist attraction, the focus of countless holiday snaps and local postcards. It even found its way on to the routes of bus tours. Annie hung collection boxes for Save the Children on the fence, quietly making her fanciful creation a force for good.

Curiously, Annie herself was rarely glimpsed. Although she took delight in people’s love of her garden and was appreciative of the shower of Christmas cards that she received from all over the world every year, she was shy of attention, and often when you stood admiring the garden, you suddenly heard her scuttling away inside the cottage. Rarely seeing her at work made the place seem all the more magical to a child, as if it all happened when no one was looking.

In 1995, Annie suffered a stroke and collapsed on the road outside her home. She stayed for a time at the Campbell Hospital in Portsoy. The local people wanted the cottage to be preserved as an attraction and as a memorial to her creativity, but Seafield Estates instead chose to sell off the land. There was some local publicity about the dispute, which unfortunately drew attention to the fact that the cottage was lying unoccupied. It was then broken into several times and vandalised. Many treasured items, including Annie’s father’s rocking chair, were stolen. Annie died on 26 September 1996, aged 85. Soon after, Craigherbs Cottage was destroyed.

The eulogy at her funeral began by expressing how her death had “deprived our community of a colourful character who was held in high esteem and with great affection”. The garden was naturally acknowledged, “and who knows what she was trying to say, something important, don’t you think, about the human spirit that is in every one of us?”

When I was researching Annie’s life, the first time I saw a photograph of this remarkable lady, with her “weather-beaten features and hard-working hands”, I realised that we had actually once met, but that I had been completely unaware of who she was. It would have been three or four years before she died, a wintry Sunday evening, on a bus taking my girlfriend and I back to Aberdeen after a weekend away. Annie got on at the stop nearest to her home and sat across from me. As we passed Craigherbs Cottage, I pointed it out to my girlfriend, and the cheerful stranger cast a knowing smile at me. She got off at Whitehills, and I was later told that she would probably have been going to get her hot water bottle filled up by a friend.

Annie now rests in Marnoch cemetery. A new house now stands on the site of Craigherbs Cottage. It is noisier there now. Passing cars are constant rather than occasional. There is no roadside carnival to stop for, no trace remaining of this ordinary piece of land’s enchanted past.

There is, however, one further piece of the jigsaw which I have located. In 1984, a Grampian Television crew visited Craigherbs Cottage while making an edition of the travelogue On the Road Again in the area. (She kept them waiting while getting her hair done.)

The two-minute item, which I have included below, sadly was shot early in the year, before the garden was in full bloom. It’s a rather insubstantial but still treasurable piece of footage, since it is the only moving image that the world has of Annie Thomson. If only, during her lifetime, someone had sat her down to tell the story of her self-sufficient existence, a tough but bucolic tale of someone clearly blessed with remarkable imagination and artistry who, rather than being unambitious, was content simply to make a gift of that mad and merry little piece of land.

My thanks to the many people who helped me to piece together the story of Annie and Craigherbs Cottage.

Fantastic story and photos We lived just outside Cullen and my Granny lived in Banff, mum used to take us in the bus and that’s how we discovered the cottage

Thank you for writing it

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful piece. I enjoyed reading this so much. It took me on such a beautiful journey.

I live in Hertfordshire and wish The Crazy Pub still existed today. Thanks for sharing such a beautiful write up on this extraordinary story, Simon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lovely story about Annie whom I knew very well when I was little as my sister and I spent a lot of time with her in her cottage. I remember so well her large work worn hands and weather-beaten features how she always loved her garden and one of her winter hobbies was making rugs from pieces of rags. Thank you for writing the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this, I actually got goosebumps reading it. I remember holidays in Portsoy and Cullen and asking my dad to stop anytime we passed by the garden. Must have some pictures somewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful and evocative tale. So important to acknowledge and establish in memory the unknown people, the people with small but important lives, and those known only to a few. Thank you for writing this.

LikeLike