For my book, A Dangerous Place, I spent a lot of time talking to officers from Surrey CID, and through that research also discovered a remarkable website detailing the history of the constabulary. It’s a fascinating, if disturbing, resource, an aural history of the last half-century of policing the county in the words of the officers themselves. Unlike those huge, high-profile cases that earn themselves books and documentaries, the site is a vivid and frightening look at the everyday business of crime, which is still, more often than not, an extraordinary business. Some of the tales recollected are routine, some inexplicable, and some read as black comedy. This is one of many which caught my attention:

1967: “Mrs Pretty stabbed her husband at their home in Chiddingfold on Christmas Day whilst rowing over who was going to carve the turkey, he was fatally killed… she had been slaving away in the kitchen preparing the Christmas dinner and her husband was watching Norman Wisdom in a variety show on TV. Norman was in great form and the husband was roaring with laughter. Mrs. Pretty was stressed out with all the work she was doing and kept telling him to stop laughing. He ignored her and she ‘lost it’ and went in to the living room and stuck him with a carving knife. Norman had a lot to answer for that Christmas!”

For some reason I was reminded of the bizarre story recently while on the way to visit the National Archives, so while I was there enquired as to whether the file on the case was now open. It is, and reading it revealed that the recollection above was inaccurate (as one would expect after more than fifty years). It took place in Haslemere, not Chiddingfold (though there is a Chiddingfold connection), happened in 1964, not 1967, and the sequence of events was in reality quite different, if almost as ludicrous as I had been led to believe. This bizarre open-and-shut case is typical of the banality, pointlessness and meaninglessness of real crime (as opposed to the elaborate plots and meaty motivations of most crime fiction). Most serious crimes are split-second occurrences which shatter lives, their after-effects spreading like stains across the years that follow and infecting the lives of even those on the peripheries.

Contained within the file are the usual forensic mixture of statements, exhibits lists, depositions, post-mortem and psychiatric reports and a transcript of the trial, which was held at Kingston Winter Assizes two months after the killing. Mrs Helen Pretty pleaded guilty to murder on the grounds of provocation.

The first piece of the jigsaw is a statement made by the accused’s sister, Elizabeth. It reveals that both girls came from a very large Irish family, and when Helen was 24, the pair moved to England. Shortly after this, Helen met (Leslie) Michael Pretty. They married in December 1962, and the following June, Helen gave birth to a son.

Although it is not remarked on anywhere in the file, the fact that their child was born only six months after the wedding would have been a much more significant fact in 1962 than it would be today. From what follows, it would suggest that the marriage was instigated by social expectations more than love.

After the wedding, the couple lodged with Michael’s parents at Prestwick Farm, Chiddingfold. Then comes this line:

“Helen often visited me without her husband. She told me on those visits that her husband used to beat her up and give her no money”.

She alleged that on two occasions while she was pregnant, Michael had assaulted her, and had marks on her arms and a lump on the back of her head to prove it. The head wound was apparently meted because she had refused to go out to buy him cigarettes. Helen was pregnant at the time of both attacks.

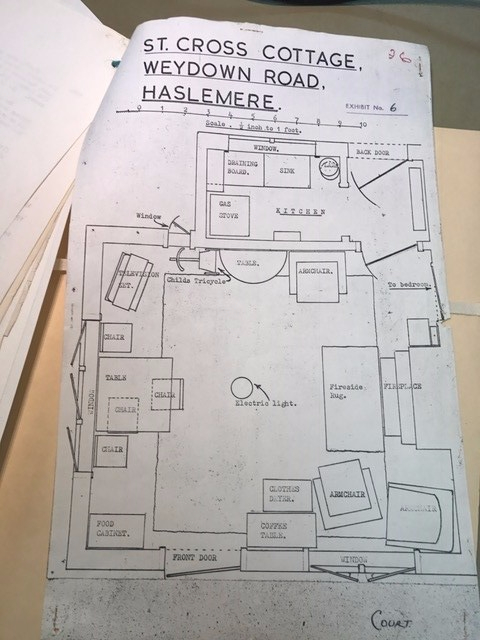

A year after the wedding, the couple moved to St Cross Cottage in Weydown Road, Haslemere. Elizabeth witnessed many verbal altercations between the pair, which Helen said were usually because he gave her so little money and because, as she perceived it, his parents disliked her.

A curious incident occurred four days before Christmas. Helen had been wanting to visit her mother in Ireland, having not been back once in the four years since she left. Michael’s family had refused to give her the passage money or look after the baby while she was gone, but her husband then stumped up the money and offered to take a week off work to look after the child. Her sister dropped her at the station, but a little later, Helen appeared back at the house, having decided against going because she was anxious about leaving her son. According to Elizabeth, “when she same in he just said ‘can I have my money back’, no word of greeting. Bizarrely as the evening progressed, the couple appeared to be getting on perfectly well with each other.

Elizabeth saw a good deal of Helen over the next few days, and said she was perfectly normal and reported no trouble at home.

On Christmas Day, “everything was quite happy during dinner”. The three watched television by the fire for a few hours, then Helen brought in a chicken from the oven for supper, a present from Michael’s parents. She asked her husband to carve while she buttered some bread. Mr Pretty was the only one to have drunk any alcohol, and he’d only had “one ale”. The couple stood at opposite ends of the dining table while Elizabeth continued watching television. BBC1 were broadcasting Norman Wisdom’s Christmas pantomime of Robinson Crusoe (which achieved what was, at the time, a record audience of 18.5 million).

“Helen appeared to be enjoying it – she likes Norman Wisdom’s films very much – they make her laugh”. Suddenly her husband told her to stop laughing. She explained she was only laughing at the television. He put down the carving knife and fork, then slapped her hard across the face. She responded with “I’ll hit you one back” and they tussled. The baby started crying and ran to Elizabeth. When she looked up again, Mr Pretty was clutching his chest and saying “I’m dying, Helen”. He fell to his knees, and despite Helen saying “don’t take any notice, he often says that when we clash”, Elizabeth said “he’s looking very pale”.

He went to the door, and Helen asked Elizabeth to telephone for a doctor. Then she noticed blood on the blade of the carving knife. Mr Pretty never regained consciousness. Helen was in “a highly distressed state” and sobbing when the police took charge of her, saying “what have I done?” and “what will happen to me?”

Those are the basic facts. But there is more significant background in the other statements.

Mr Pretty’s father claimed that while the couple lived with them, Helen “spent most of the time in her room, watching television or listening to the radio”, and never helped his wife with the housework.

There were also a number of reports from local police officers and the family GP, all of whom had been called to the Prettys on a number of occasions because of violent arguments. On one occasion, Helen was drunk and in a ferocious temper, smashing up the living room. In her doctor’s words, she was “fighting mad” because her husband had left her and she had reacted by drinking all the alcohol in the house while in charge of her child.

In June 1964, a police officer arriving at the house was told by Helen that an argument had started because “he would not take me to the pictures. I never go out anywhere and he does not give me much money”. After her husband left the room, she continued: “he is always hitting me even when I was pregnant”. When Michael came back in with a dustpan and brush to clear away the broken glass, Helen laughed at him, and he told the police: “she even tore up the kiddy’s birthday card from my mother”.

Judging the situation as a “domestic”, the police advised Mrs Pretty that if she had a genuine complaint to make about her husband, it should be made to a solicitor.

On another occasion, two months before his death, Michael arranged to see a divorce lawyer; Helen again began to vandalise the house and, to stop him keeping the appointment, threw his shoes on the fire. On this occasion, Michael said to the police officer “can’t you do something?” However, by the time the officer left, the couple appeared to be at peace again. Volatile would be a diplomatic way to describe such a relationship.

Three weeks after the crime, Helen was examined by a psychiatrist while on remand at Holloway. He discovered that she had a mental age of eight, was “a subnormal girl who requires some form of guidance and help” and was “emotionally immature with a rather inadequate personality”. She admitted to “crying on the slightest pretext”, but the doctor did note that despite her “mental subnormality… she has been able until recently to cope with the exigencies of life, namely that she has looked after a home and a baby”, and had previously worked as a domestic in a hospital.

A further, more detailed report revealed that Helen had been incapable of managing the house-keeping, which is why her husband controlled all the money in the house, and that her husband “had to do most of the cooking too”. The report also added that she was incapable of comprehending simple facts and was “lacking in forethought, to the extent that she is unable to judge the consequences of her actions”. It concluded that “coupled with her mental subnormality there is considerable emotional immaturity, together with an inadequate personality. She has also a recent history of an aggressive outburst in the course of which he husband was killed. In these respects she is in need of training and guidance in a hospital for the mentally subnormal”.

The final notes, headed “antecedents”, give a scant biography of Helen’s otherwise unremarkable life. Each employer she had before her marriage described her as hard-working; one went as far as to call her “an excellent worker of excellent character”, though another noted she was “very quick-tempered”.

Helen Pretty was detained at a mental hospital; her baby was taken into care.

Although cold, emotionless official paperwork is devoid of judgement, many of the facts listed in this depressingly ordinary, senseless story read differently to us in 2017 to how many people would have perceived them in 1964. As soon as I came across the first reference to Helen complaining that her husband beat her, I immediately began to see this as the story of an abused woman finally fighting back and inadvertently killing her monstrous abuser. In 1964, such matters would have been looked on by many as nothing like as horrific. No less a symbol of decency and integrity than PC George Dixon of the fictional television series Dixon of Dock Green infamously and lightly told viewers in the 1956 episode Pound of Flesh that “if I arrested every bloke in Dock Green who clocked his wife, I’d be working overtime”.

Although cold, emotionless official paperwork is devoid of judgement, many of the facts listed in this depressingly ordinary, senseless story read differently to us in 2017 to how many people would have perceived them in 1964. As soon as I came across the first reference to Helen complaining that her husband beat her, I immediately began to see this as the story of an abused woman finally fighting back and inadvertently killing her monstrous abuser. In 1964, such matters would have been looked on by many as nothing like as horrific. No less a symbol of decency and integrity than PC George Dixon of the fictional television series Dixon of Dock Green infamously and lightly told viewers in the 1956 episode Pound of Flesh that “if I arrested every bloke in Dock Green who clocked his wife, I’d be working overtime”.

The acknowledgement that Mr Pretty “had to do most of the cooking himself” was clearly something to remark upon in those times, too. And today, a shotgun wedding is not the first reaction to an unmarried woman’s pregnancy. Here it glued together two people who were clearly destined to tear each other apart.

Today, Prestwick Farm, nestled in one of the richest and most picturesque of Surrey parishes, offers four-star self-catering accommodation as well as organic produce. St Cross Cottage, in the early 1900s home to the weaving quarter of the Peasant Arts Movement, has long since been demolished. Most of the players in this sorry story are probably now long dead.

But it did occur to me, as I handed the file back, and thought that perhaps no one will ever again have any cause to seek it out, that perhaps one day, a middle-aged man might walk into the National Archives and order it up. Then, after studying its contents in a quiet corner for an hour, he might return it to the librarian, and then, as he walks back out into the world, think to himself:

“Well, now I know what happened to my parents”.

Interestingly there was a lot of last telling of females being mentally subnormal in the early to middle 20th century. Most of which would see you end up in a mental institute, most of which would be a convenient explanation to what we would now see as hormonal behaviour or just women standing up for themselves. We can’t discount the fact that the police would have viewed her in a typically derogatory fashion due to her gender based on the timeline. Had this been in current times, it might have been viewed differently and her complaints might (or might not) have been treated more seriously and the eventual death could have been mitigated. She could very well have just been completely mad too, but it’s important to recognise the possible distinction.

LikeLike