This is a story not only about a forgotten story, but about a forgotten tragedy. It is a two-part tale. Bear with me.

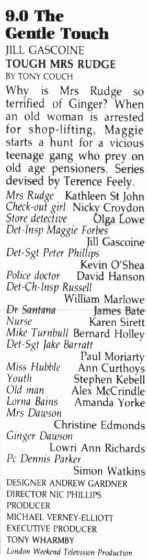

In the ever-changing sea of crime series, one of the better remembered but lesser-valued is LWT’s The Gentle Touch (1980-84), which history will probably acknowledge merely for  being the first British police drama to be headed by a woman, namely DI Maggie Forbes, played by the similarly underrated Jill Gascoine. The Gentle Touch was in fact a fine series, which, unlike most of its contemporaries, was more interested in victims than criminals, more interested in the causes and effects of crime than in its detection, a tragic pursuit well reflected in its melancholic closing theme music . In this respect it had more in common with the early episodes of Z Cars than with the recent move towards filmed, action-based series such as The Sweeney. Set at a fictional nick in Seven Dials, it impressively expressed many of the concerns of its day: youth crime, sexism and racism on the streets and in the police force, domestic violence and homophobia.

being the first British police drama to be headed by a woman, namely DI Maggie Forbes, played by the similarly underrated Jill Gascoine. The Gentle Touch was in fact a fine series, which, unlike most of its contemporaries, was more interested in victims than criminals, more interested in the causes and effects of crime than in its detection, a tragic pursuit well reflected in its melancholic closing theme music . In this respect it had more in common with the early episodes of Z Cars than with the recent move towards filmed, action-based series such as The Sweeney. Set at a fictional nick in Seven Dials, it impressively expressed many of the concerns of its day: youth crime, sexism and racism on the streets and in the police force, domestic violence and homophobia.

Predominately a studio-based drama, The Gentle Touch was necessarily blessed with sensitive writers, in particular PJ Hammond, whose skill at exploring vulnerable personalities at crisis point had already been well-demonstrated in series such as Thames’s Couples (1976) and LWT’s women-in-prison saga Within These Walls (1974), and would find its best expression in the emotional ghost stories of his series Sapphire and Steel (1979-82). Although The Gentle Touch was always watchable and frequently excellent, its finest hours are two scripts by Hammond, Damage, the tale of a neurotic single dad, abandoned by his wife and the victim of a hate campaign by his seemingly-respectable neighbours, and Solution, in which a young lesbian dying of leukaemia asks her lover to assist in her suicide, Kenneth Ware’s devastating Pressures, in which the usually impervious DCI Russell (William Marlowe) finds himself on the verge of a breakdown (an episode which echoes John Hopkins’ most tortured walks into the dark on Z Cars), and the episode I will be examining here, for reasons which will become apparent: Antony Couch’s shattering Tough, Mrs Rudge.

would find its best expression in the emotional ghost stories of his series Sapphire and Steel (1979-82). Although The Gentle Touch was always watchable and frequently excellent, its finest hours are two scripts by Hammond, Damage, the tale of a neurotic single dad, abandoned by his wife and the victim of a hate campaign by his seemingly-respectable neighbours, and Solution, in which a young lesbian dying of leukaemia asks her lover to assist in her suicide, Kenneth Ware’s devastating Pressures, in which the usually impervious DCI Russell (William Marlowe) finds himself on the verge of a breakdown (an episode which echoes John Hopkins’ most tortured walks into the dark on Z Cars), and the episode I will be examining here, for reasons which will become apparent: Antony Couch’s shattering Tough, Mrs Rudge.

All television drama series quickly establish their tone, their vocabulary, their politics and their parameters. A challenge for drama producers is to keep the viewer surprised but never disorientated. But occasionally, a genre series throws up an episode that successfully takes us out of its established comfort zone. It can be an unsettling feeling, that sense that this week “the goodies just might not win”.

Tough, Mrs Rudge begins with a forlorn old lady trailing around a shop and being accused of stealing a pint of milk. One could be forgiven for thinking this is not going to be a crime story of any great significance.

But when, while being questioned by the police, Mrs Rudge is examined by a doctor, he discovers burn marks on her arms, caused by a lit cigarette being held against the skin for several seconds. She also appears to be suffering from malnutrition, and only has 22 pence in her purse. When asked if she has any family, she says “me son went to Australia just after the war. He used to write regular, every month”.

She refuses to remain in hospital, anxious to get back to her flat. Maggie offers her a lift which she reluctantly agrees to, but says: “just take me as far as the street. Nobody’s going no further than that”.

After an exasperating phone call to the social worker who covers the area, and who hasn’t seen Mrs Rudge for two years, Maggie wonders “how is it we can never look after the old women who get beaten but we’ve always got plenty of time, money and colour tellies for the ones who do the beating?”

After an exasperating phone call to the social worker who covers the area, and who hasn’t seen Mrs Rudge for two years, Maggie wonders “how is it we can never look after the old women who get beaten but we’ve always got plenty of time, money and colour tellies for the ones who do the beating?”

Back in hospital some days later after collapsing and nearly being hit by a bus, Mrs Rudge falls into a coma. The doctors discover shocking new injuries: heavy bruising on her back suggests she was kicked several times. Maggie’s revulsion is beginning to cloud her judgment; when she returns to the hospital to be told the old lady has died, the revulsion turns to fury. Standing in the graffiti-covered wreckage of Mrs Rudge’s flat, Maggie is told by the social worker that the youngsters who presumably did this: “have to live in the society we make for them. They’re as much the victims as Mrs Rudge. You know what it’s like around here. Concrete and tarmac and everyone on the make from top to bottom. They don’t give a damn about the young. When something like this happens, everyone turns on the kids. They didn’t ask to be brought up in this rat trap”. But as Maggie points out, “this is not about mischief or petty crime. This is sadism”.

and tarmac and everyone on the make from top to bottom. They don’t give a damn about the young. When something like this happens, everyone turns on the kids. They didn’t ask to be brought up in this rat trap”. But as Maggie points out, “this is not about mischief or petty crime. This is sadism”.

There are just two clues to the attackers: in her few moments of consciousness before she died, Mrs Rudge was captured on tape deliriously reliving her ordeal, saying “don’t come near me, Ginger. Take anything… but go away”. Also, a piece of green shoe leather is found in the flat, suggesting one of the gang was a girl.

The girl in question, Lorna Baines, is arrested while attempting to mug an old lady for her pension. Once in custody, she refuses to cooperate, and it becomes clear that it is not the police she is scared of, but someone else. When the realisation dawns on her that the reason she has not been asked to take part in an identification parade is because Mrs Rudge is dead, she reluctantly names her accomplices (all girls), and finally, fearfully, the leader, Ginger Dawson.

The girl in question, Lorna Baines, is arrested while attempting to mug an old lady for her pension. Once in custody, she refuses to cooperate, and it becomes clear that it is not the police she is scared of, but someone else. When the realisation dawns on her that the reason she has not been asked to take part in an identification parade is because Mrs Rudge is dead, she reluctantly names her accomplices (all girls), and finally, fearfully, the leader, Ginger Dawson.

Up until now, Tough, Mrs Rudge has played out as a distressing, well-acted piece of crime drama which impresses with its sense of outrage and injustice, and alarms with its tough, end-of-its-tether attitudes, armed with a storyline that taps into real fears of its era about a seemingly lawless new wave of youngsters. Amanda York is particularly effective as the feral, hateful Lorna. But what follows in the episode’s final act is a scene that catapults us into another realm, less familiar and more frightening.

Whatever we might be expecting is confounded when Ginger finally appears; the sparse writing, the acute direction and the eerie performance of Lowri-Ann Richards make this single  scene extraordinarily disturbing. Ginger silently rocks back and forth on a chair in the interview room, utterly disengaged, unmoved and unperturbed by her surroundings. Whatever we might have expected, she is not it. “You’ll have to talk when you get into court, and that’s where you’re going,” Russell tells her. “Judges regard silence as contempt. They don’t like it. They hate it”.

scene extraordinarily disturbing. Ginger silently rocks back and forth on a chair in the interview room, utterly disengaged, unmoved and unperturbed by her surroundings. Whatever we might have expected, she is not it. “You’ll have to talk when you get into court, and that’s where you’re going,” Russell tells her. “Judges regard silence as contempt. They don’t like it. They hate it”.

As he makes to leave, finally she speaks.

“Hey. And I hate them”.

If this is an attempt at establishing a plea of diminished responsibility, it’s unlikely to succeed, because she has been far too careful: a calculated campaign of terror to force an old lady to hand over her pension. “The fact that you behaved like something that crawled out from under a stone isn’t going to help”, says Maggie.

Silence.

Then we cut to a wide shot as Ginger, her foot resting on the table, sends it hurtling across the room.

The officers look down at her, simply unable to comprehend what they are dealing with. As Maggie orders her to be taken back to the cells, Ginger speaks once more, playfully:

“Hey you. Tea. I wanna cup of tea. You gotta give it to me. I got rights”.

Maggie puts down her notepad, incredulous.

“Stand up,” she orders.

“Go and screw yourself,” comes the reply.

Maggie grabs her and pulls her to her feet. But as she looks into the girl’s eyes, she can find nothing, no humanity, no sense, no explanation. All she can do is storm  out, insisting: “No tea. No nothing”. Ginger continues to rock back and forth on the chair, half smiling.

out, insisting: “No tea. No nothing”. Ginger continues to rock back and forth on the chair, half smiling.

Maggie is then told that the medical report on Mrs Rudge’s death puts the cause of death as a heart-attack, but says the causes are “not determinable”. It would be impossible to prove conclusively that the death was murder and not the result of an existing heart condition.

It is an exceptionally bleak ending, and, in what looks like an intervention from someone other than the writer, it is only slightly weakened by a deus ex machina seconds before the end credits in which another elderly resident who was a victim of the gang comes forward, prepared to give evidence against Ginger.

The director of Tough Mrs Rudge was Nic Phillips. “What an amazing training multi-camera drama like this was for doing soap, which I do today, because it was predominantly dialogue, not action” he says. “The Gentle Touch was an issue-driven series, with a group of characters putting service before friends and family, and I can see how coming out of the craziness of the 1970s, that was how they wanted to steer it. There was a constant theme of police officers sacrificing their family life for their work.

“Jill was charming, and very good at what she did. She used those glittery eyes, and when her character was anxious her head would sink into her shoulders. I remember the producer, Michael Verney-Elliott, would sometimes just shout to her “Jill, no neck monster!” and she would change shape.

“William Marlowe was brilliant. A very focused actor; some actors , when they are on set, they just command. He was a charming, gentle man, but he delivered this very clipped, quite stylised performance”. Marlowe is indeed strikingly good as the demanding, seen-it-all copper with an intimidatingly-powerful moral centre. “Kenneth Ware, who wrote Pressures, wrote this curious dialogue, with phrases chopped off, things like ‘who am I to look a gift horse’, a slightly American feel to it perhaps, but it worked well. Bill then started writing episodes himself, under a pseudonym, Neil Rudyard, which were often slightly comic, and which were a breath of fresh-air for all of us in what was generally quite an intense series”. (Marlowe had in fact been spotted earlier in his career by Stanley Baker, who cast him in the wonderful Robbery (1968) and was determined to turn him into the next Michael Caine, but Marlowe was not interested in being that kind of star, and instead became a reliable television player, usually playing either a cop or a robber.

“William Marlowe was brilliant. A very focused actor; some actors , when they are on set, they just command. He was a charming, gentle man, but he delivered this very clipped, quite stylised performance”. Marlowe is indeed strikingly good as the demanding, seen-it-all copper with an intimidatingly-powerful moral centre. “Kenneth Ware, who wrote Pressures, wrote this curious dialogue, with phrases chopped off, things like ‘who am I to look a gift horse’, a slightly American feel to it perhaps, but it worked well. Bill then started writing episodes himself, under a pseudonym, Neil Rudyard, which were often slightly comic, and which were a breath of fresh-air for all of us in what was generally quite an intense series”. (Marlowe had in fact been spotted earlier in his career by Stanley Baker, who cast him in the wonderful Robbery (1968) and was determined to turn him into the next Michael Caine, but Marlowe was not interested in being that kind of star, and instead became a reliable television player, usually playing either a cop or a robber.

Turning to the character of Ginger, Phillips says that “when you’re shooting something like that interrogation scene, it’s best to keep things simple. A bare room, a table and chairs. Because most of all it’s about the acting, and those two girls were marvellous”.

“That job more or less kick-started my career”, remembers Lowri-Ann Richards. “After drama school, I was in various New Romantic bands, and wore my own clothes and make-up for the part. My agent wasn’t someone who gave praise lightly but she did praise me for that performance. And ten years later I put the clip of that scene on a showreel, and off the back of it I got a Hollywood agent.

drama school, I was in various New Romantic bands, and wore my own clothes and make-up for the part. My agent wasn’t someone who gave praise lightly but she did praise me for that performance. And ten years later I put the clip of that scene on a showreel, and off the back of it I got a Hollywood agent.

“It was probably Nic who suggested rocking on the chair and making that drumming sound. It gives that scene another dimension, an extra edge. But also, regarding the way I looked, I must have walked into the interview like that. I mean I’m not sure someone like Ginger would necessarily have looked like that, with eyeliner so quite delicate and precise”.

In fact, it is precisely her unexpected appearance and behaviour that make the character so intriguing. Rather than looking too exotic, it actually underlines the character’s acquisitiveness, her obvious desire to elevate herself from her surroundings. Her strange contentment after her arrest and her intimidating performance when being questioned suggest someone living her life as her own work of art.

“Now that is fascinating”, says Lowri-Ann. “Like the centre of a drama of her own making, creating her own world and her own legend? Perhaps that aspiration and other-worldliness is a bit like Sting’s character in Quadrophenia”.

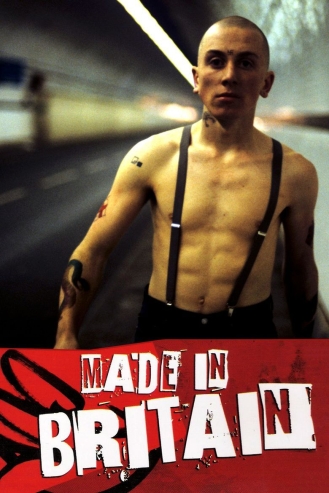

It is, in fact, depressingly common for young criminals to react to feelings of inadequacy by imagining themselves as malevolent heroes of their own dramas. In my book A Dangerous Place, I mention how David Mulcahy, the “railway killer”, inspired by a warped interpretation of martial-arts ideology, saw himself as an “immortal warrior”, and felt “God-like” when committing murder. In the case of the “Red Riding Hood Murder”, 21-year-old David Smith committed the motiveless slaughter of a child; found in his bedroom were notes fantasising further offences and imagining himself as a master-criminal. And in fiction, the same year as Tough, Mrs Rudge, David Leland’s celebrated Made in Britain starred Tim Roth as Trevor, an intelligent, violent skinhead who, at 16 years old, has consigned himself to a life of incarceration and deprivation, but paradoxically insists that in his rejection of the world around him, “I’m a success. I’m a fucking star”.

It is, in fact, depressingly common for young criminals to react to feelings of inadequacy by imagining themselves as malevolent heroes of their own dramas. In my book A Dangerous Place, I mention how David Mulcahy, the “railway killer”, inspired by a warped interpretation of martial-arts ideology, saw himself as an “immortal warrior”, and felt “God-like” when committing murder. In the case of the “Red Riding Hood Murder”, 21-year-old David Smith committed the motiveless slaughter of a child; found in his bedroom were notes fantasising further offences and imagining himself as a master-criminal. And in fiction, the same year as Tough, Mrs Rudge, David Leland’s celebrated Made in Britain starred Tim Roth as Trevor, an intelligent, violent skinhead who, at 16 years old, has consigned himself to a life of incarceration and deprivation, but paradoxically insists that in his rejection of the world around him, “I’m a success. I’m a fucking star”.

“I wasn’t terribly politically aware at the time.” says Lowri-Ann, “In some ways it was a very ‘me me me’ world, the music scene, but there was a heaviness around at that time, queer-bashing, football violence, lots of stuff in the press about hooligans. There was a certain element of danger, but of course when you’re in a band, you’re in a gang yourself, you feel invincible, unlike the little Mrs Rudges of this world, who are all alone”.

So much for Tough, Mrs Rudge, an exceptional episode of a good series. Why should it be considered as anything more than that?

Because, to the surprise of both Nic and Lowri-Ann, it was a true story.

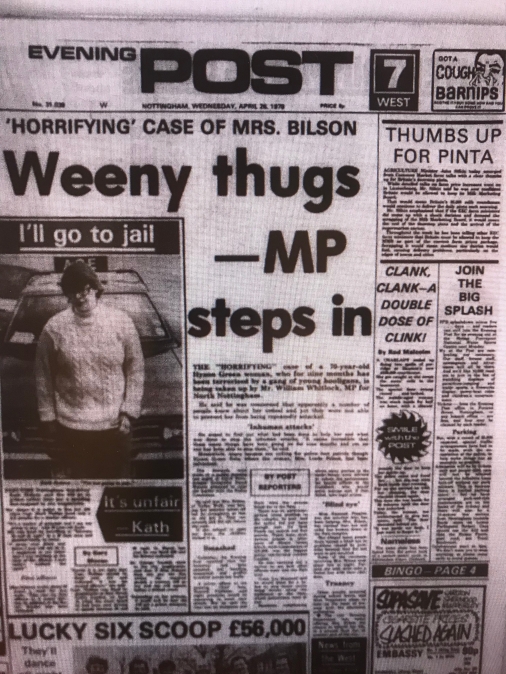

It happened in Nottingham, in 1978, on a notorious estate named Hyson Green (and renamed Hill Green in Tough, Mrs Rudge). While conceived and sold as a utopia to replace slum housing, its local Tesco opened by Crossroads star Noele Gordon, Hyson Green was a brutal (and Brutalist) example of the reality of the new housing estates of post-war Britain. With a population of 101,000, it was the most populous and problematic police district in the city.

The two most famous high-rise estates in Britain were probably London’s Trelllick Tower and Ronan Point. The latter opened in 1968; two months later a gas explosion caused one entire corner to collapse. High-rise living, on paper, was thought to be the solution to Britain’s housing problem, but corrupt deals between local councils and building companies, as well as sociological pitfalls (some of which were unforeseen, some of which were preventable) made places like Trellick shrines to crime by the end of the 70s, the press reporting stories of women being assaulted in the lifts and, on one of the numerous occasions when the lifts weren’t working, an elderly resident dying after returning with his shopping and suffering a heart-attack climbing the stairs on Christmas Eve.

“It took a hundred years for what our ancestors built to turn into slums, and it’s taken just ten years for Hyson Green to turn into a modern slum,” were the words of a BBC news report. In the middle of the chaos there, at 22, Valley Walk, lived a 70-year-old widow, Linda Bilson: the real Mrs Rudge.

Her ordeal began with a group of children, either by their trickery or her trust, acquiring  a key to her flat. “They seemed like nice kids and I trusted them,” she later said. It was the beginning of nine months of persecution. At first they offered to run errands for her, but never returned with the cash or the goods. When she started to refuse them entry, they kicked her door in. As well as robbing her repeatedly of her pension, they also tortured her and vandalised her flat.

a key to her flat. “They seemed like nice kids and I trusted them,” she later said. It was the beginning of nine months of persecution. At first they offered to run errands for her, but never returned with the cash or the goods. When she started to refuse them entry, they kicked her door in. As well as robbing her repeatedly of her pension, they also tortured her and vandalised her flat.

Just before Christmas 1977, she collected a double-helping of pension to see her through the holiday period, £54.28, which they stole from her, squabbling over the share-out in the process. Local bobbies visited her at  Christmas and gave her wine and mince pies. But a few months later, the violence reached such extreme levels that local MP William Whitlock became involved in the case. Nine youngsters appeared in the juvenile court, the press reporting that they had kicked the old lady in the knees and on her back, twisted her arms and fingers and cut her hair. One of them had even urinated on her.

Christmas and gave her wine and mince pies. But a few months later, the violence reached such extreme levels that local MP William Whitlock became involved in the case. Nine youngsters appeared in the juvenile court, the press reporting that they had kicked the old lady in the knees and on her back, twisted her arms and fingers and cut her hair. One of them had even urinated on her.

The council offered Mrs Bilson accommodation in an old peoples’ home, but she refused to move. The youngest boy’s solicitor argued in court that he lived “in overcrowded conditions with nowhere to escape. He mixed with restless and bored children and he is easily led”. But the chairman responded that “thousands are living in the same conditions you are. Your parents have tried their best to ensure you have a  good home. You are a cunning individual”. The boy who was charged with indecent assault (a charge that was subsequently dropped), when asked why he had slapped Mrs Bilson and ripped the stuffing from her settee, said he “enjoyed seeing her become annoyed”.

good home. You are a cunning individual”. The boy who was charged with indecent assault (a charge that was subsequently dropped), when asked why he had slapped Mrs Bilson and ripped the stuffing from her settee, said he “enjoyed seeing her become annoyed”.

Most of the boys were given short stays at detention centres; one girl was placed in the care of the local authority and the others received fines.

Linda Bilson was epileptic, and at this point was suffering up to six attacks in a day. Two months later, a neighbour, who hadn’t seen her for two days, entered her flat and found the heating full on, the windows closed and Linda, fully-dressed and wearing an overcoat, lying on the floor. She was dead. The coroner returned a verdict of natural causes.

In 1981, rioting adding to the depressing list of crimes at Hyson Green, which also included prostitution and drug taking. Four years later, the council admitted defeat, and pulled the entire estate down. Today it is the site of a vast Asda supermarket. Recently, a National Lottery grant sponsored a local history project remembering Hyson Green and capturing residents’ memories. When they were published, there was not one single mention of Linda Bilson.

To the right-wing press, the case of Linda Bilson was a story of indiscipline, lawlessness and depravity. To the liberals, it was sickening proof of the worst extremes of what can happen when vulnerable people are packed together in inhospitable spaces, and they,

and their children, are abandoned by the state. In Tough, Mrs Rudge, the diagnosis of “moral imbecility” is mooted; Sgt Phillips, who represents the new breed of idealistic, degree-educated fast-track policeman, is asked for his reaction to the term, and even he can now only interpret it as “vicious little bastards”.

Whichever side of the issue one comes down on, it is impossible not to apportion some blame to those who got rich off the poor when designing cheap, shoddy, inhumane estates. Both Tough, Mrs Rudge and the case of Linda Bilson are forgotten stories today, but both deserve to be remembered, one as a tragedy, and one as a vivid example of how, through genre television, a writer can share with millions of people something that on this occasion he clearly couldn’t ignore, but equally he couldn’t understand.

My thanks to Nic Phillips and Lowri-Ann Richards for sharing their memories.

An exemplary article, that looks at the episode through several different lenses, each bringing another aspect into focus.

What do we know of Anthony Couch? Looking at his credits, I must have seen about half a dozen of his scripts, but I’d never really registered the name before. He first appears co-writing a Saturday Matinee play on the Home Service in 1953 while his final credit is for an episode of Perfect Scoundrels in 1991.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Six years late(r), just wanted to say I appreciated the research that went into writing this article. A fascinating glance into the all-too recent past and the way in which such seemingly ephemeral cultural artefacts of the day can illuminate our social history.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for those kind words.

LikeLike